it is well with my soul

What kind of relationship do you enjoy, right now, with your own emotionally charged experience? I mean: all this hurt, tiredness, joy, agitation, sorrow, worry, delight, anticipation, dread, guilt, shame, buoyancy, chutzpah: do you accept and honour it as a moment in the rolling seascape of your soul, or do you instead feel badly about (some of) it? Do you rebel against it and yourself? Do you wish it away? Do you think less of yourself for having it? Are you relentlessly struggling against it?

Horatio follows right away and, mid-way across the Atlantic, is summoned to the bridge by the captain - who tells him that they are now over the site where his family perished. Returning to his cabin he's inspired to write the words of the hymn "It is well with my soul". Here's the first verse:When peace, like a river, attendeth my way,

When sorrows like sea billows roll;

Whatever my lot, Thou hast taught me to say,

It is well, it is well with my soul.

Later it was set to the tune Ville du Havre by the composer Philip Bliss:

Though Satan should buffet, though trials should come,

Zenists, Stoics, 3rd wave CBTists, and sundry others tell us something like this: We can't control the 'first arrow' of the pains that life inexorably throws our way. What we can learn to relinquish, however, is the shooting of that 'second arrow' that we then reflexively shoot at ourselves: our reaction to our reaction. Passing sadness or worry get augmented into ongoing depressed mood when we refuse to accept them. Prolong this further and we arrive at what used to be called 'neurosis': the mind becoming perennially allergic to itself, caught up in inner battles with inner phantasms, no longer enjoying an open relation to the world. Left to themselves, however, and the first arrows soon enough drop out and our wounds heal over.

In this brief Lenten post I want to retell the story of Horatio Spafford (born 1828) and the extraordinary moment of acceptance he achieved in the midst of great tragedy. Part of my reason for sharing it is to help resist the temptation to think that it's only if we go back to (the indubitably valuable resources of) pagan antiquity or the Buddhist east that we can find what we need to help us hold back the second arrow. (There may of course be aspects of the Christian faith that, as you see them, put you off from engaging with what else it has to offer! But my point here is simply to emphasise an aspect of the wisdom it does contain.)

Horatio was a 'successful' American lawyer and property dealer who married his Norwegian wife Anna Larsen when he was 33 and she 19. Even before the fateful voyage of which I'll shortly tell, they suffered tragedy: the great fire of Chicago in 1871 destroyed most of his investments, and their son, little Horatio, died aged 4 from Scarlet Fever. The Spaffords decide to vacation in England, but at the last moment some important business affairs to do with the great fire hold Horatio back from boarding the Ville du Havre; he will follow Anna and their four daughters Annie, Maggie, Bessie and Tanessa (12 yrs - 1 yr) in a few days.

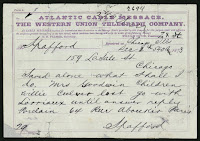

Mid-way through their journey, their steamship is struck by an iron sailing ship; Anna huddles and prays with her daughters; the boat sinks. Several hours pass and Anna is found unconscious, floating on a piece of wood. The children have all perished. One of the ministers with whom she was travelling remembers her saying “God gave me four daughters. Now they have been taken from me. Someday I will understand why.”Rescued and taken now to Cardiff in Wales, Anna telegrams Horatio: "Saved alone; what shall I do?"

|

| the Ville du Havre |

When sorrows like sea billows roll;

Whatever my lot, Thou hast taught me to say,

It is well, it is well with my soul.

Later it was set to the tune Ville du Havre by the composer Philip Bliss:

What I want now to note is how familiarity with a culture and a faith can breed blindness to its human significance. The clear message of Spafford's hymn is one of taking up an attitude toward one's soul which connotes its inner movements as in themselves well. Whether he's feeling deep peace or unspeakable sorrow: all is well with my soul. The soul is working as it should. The second arrow can be left in the sheath.

Let this blest assurance control,

That Christ hath regarded my helpless estate,

And hath shed His own blood for my soul.

My sin, oh the bliss of this glorious thought!

My sin, oh the bliss of this glorious thought!

My sin, not in part but the whole,

Is nailed to His cross, and I bear it no more,

Praise the Lord, praise the Lord, O my soul!

Praise the Lord, praise the Lord, O my soul!

Our first thought might be puzzlement: why has Spafford switched registers so quickly from talk of the trials of our lives to Christ's redeeming crucifixion? And what's this odd insistence anyway of linking a 2000 year old crucifixion to my own suffering now? Well, here's one simple thought: rather than perseverate on the idea of whether I ought to have thought or felt as I did, I can think instead on how all can again be well with my soul if I acknowledge my sin and turn to follow the redemptive light of Christ. This slate-cleaning is, in other words, all the motivation and understanding we need to not release a further kind of second arrow. Accept or reject the Christian theology - that's for you to decide for yourself. But notice the significance of sin's registration here: when I introduced the topic of the two arrows I talked of 'life' throwing the first one at us. The fact, however, is that often enough what pains us is not what life throws at us, but what we throw at it. It's this other, further, more encompassing, redemptive message of the cross, our forgiveness for as it were piercing Christ's side, of which Spafford's hymn speaks. So whether or not our first-order thoughts and feelings are in moral order yet anyway painful, or instead manifest temptation and so pain our conscience: trust in God's love for us, trust in our essential lovableness, and we can once again move past our transgressions and bear life's tribulations.

For bear them the Spaffords did. Another Horatio, a Bertha, and a Grace were born soon after. Then this little Horatio also died - of Scarlet fever at the age of 3. Finally pater Horatio moved away from his worldly interests (what we call 'success') and the family moved to Jerusalem where they founded the American Colony. This establishment carried out philanthropic work to people of all faiths in Jerusalem, establishing soup kitchens, orphanages and hospitals. Its mission continued until the Second World War.

Horatio died of malaria in 1888; Anna continued with her philanthropic work in Jerusalem until she died in 1923. They were both buried in the Protestant cemetery on Mount Zion. Eternal rest grant unto them O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon them; may all be well with their souls.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comment here!