feel and deal

I've been reading Lee Braver's Groundless Grounds - A Study of Wittgenstein and Heidegger (and, thankfully, having a better time of it than Tim.) One topic of the first chapter is Wittgenstein and Heidegger's respective take on the means to secure happiness (pp. 40-46).

I've been reading Lee Braver's Groundless Grounds - A Study of Wittgenstein and Heidegger (and, thankfully, having a better time of it than Tim.) One topic of the first chapter is Wittgenstein and Heidegger's respective take on the means to secure happiness (pp. 40-46).As Braver reads the early Wittgenstein, here we have a philosopher who sees attempts to become happy by achieving our desires as a 'sucker's game', since the world is always changing and is largely out of our control. As one of Braver's many lovely metaphors has it 'The dice are loaded - determined, even - and the house always wins in the end. Even the most fortunate face the inescapable sufferings endemic to human life.' And so we do best - in Schopenhauerian, Buddhistic mode - to withdraw from the game, quiet the will, accept how things turn out, rise above the 'circulation of pleasures and pains', disidentify with the desirous and dying body, and see the world sub specie aeterni. In this way one becomes 'absolutely safe': nothing can harm you - nothing can even befall you - since who you are is not something which sets itself over against what can happen. The Ego Ideal collapses back into the Ego.

In an earlier section of the book Braver describes the commonalities between the early Heidegger and the later Wittgenstein on the significance of absorbed coping, praxis, automaticity, the tacit, the ready-to-hand. If we lose sight of this we wrongly project the form of attention and thought deployed in philosophical reasoning - disengaged, reflective, contemplative, calculative, present-at-hand - onto our basic epistemic situation - and thereby generate unnecessarily for ourselves a whole host of sceptical problematics and banalising and intellectualised versions of the human condition. But as Braver also notes, whilst the first half of Being and Time constitutes a paean to Dasein's praxical immersedness, the latter half praises the authentic moment of choice when I pull back from an automated immersion in taken-for-granted

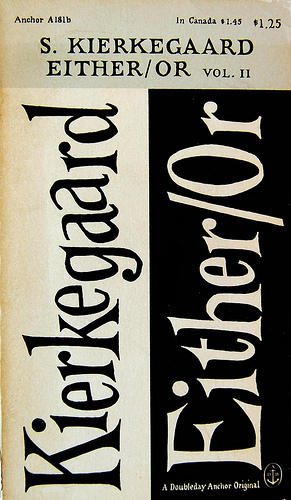

communal structures of meaning, and make a decision regarding how myself to live, what to do, coming off auto-pilot: becoming a pure moment of will. So whereas 'Wittgenstein warns us against willing, Heidegger presses it upon us, echoing Kierkegaard's Judge William's exhortation to make the most fundamental choice - choosing to choose, to make decisions deliberately rather than coasting on the inertia of our community and our past'.

communal structures of meaning, and make a decision regarding how myself to live, what to do, coming off auto-pilot: becoming a pure moment of will. So whereas 'Wittgenstein warns us against willing, Heidegger presses it upon us, echoing Kierkegaard's Judge William's exhortation to make the most fundamental choice - choosing to choose, to make decisions deliberately rather than coasting on the inertia of our community and our past'.In this chapter Braver offers us no reconciliation. But we need one, don't we? We've all met people who are so radically afflicted by passive merely-watching-their-life will-less-ness, or by angry omnipotent will-full-ness (and we all have moments of these ourselves) that they either don't really exist or live a life of futile frustration! And the answer surely isn't some banal 'everything in moderation' or vapid hodgepodge - some humdrum bio-psycho-socio-spirituo gooey fudge for the soul.

The answer, as I see it, comes from the stoics. The fundamental question to be asked, in any situation, is: What is, and what is not, within the purview of my will? To what must I reconcile myself, and yet about what can I act? How can I be clear about this, not engage in shadow boxing but be no more passive than is required? In this way we can achieve the fullness of agency that comes from seizing what can be seized, and the releasement (Gelassenheit) that comes from not railing narcissistically against the gods. These two are in fact radically complementary: when I stop directing my energy into futile tantrums against the inevitable I have all the more of it available for fruitfully and rewardingly actively discharging my duties to myself and to others. And psychodynamic psychotherapy adds a further inflection. When it comes to the inner world, what enables us to engage in courageous action is first to take the courage to put down defences and in-actively suffer, simply absorb the living meaning of, feel, our feelings - feelings being our most fundamental manner of grasping the meaning of the changes in our relationships, prospects and projects.

|

| Diana Fosha |

It takes courage to act (deal), and it also takes courage to suffer (feel) - and it takes a mindful courage to recognise the difference.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comment here!